获得性免疫血小板减少症:病理生理学、诊断与治疗新进展

引言

获得性血小板减少症(AITP)发生是由于外周血血小板丢失或消耗超过骨髓巨核细胞产生的血小板数量所致。尽管引起血小板减少的原因很多,但主要分为四类:(I)血液稀释;(II)血小板消耗;(III)血小板生成减少;(IV)免疫介导的血小板聚集增多[1]。

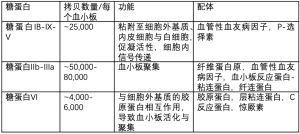

AITP是由于产生了抗血小板抗体,如自身抗体(AAbs),同种抗体或药物依赖性抗体(DDAbs)等,而这些抗体均可诱导血小板寿命缩短,临床上分别称为免疫性血小板减少症(ITP),肝素诱导性血小板减少症(HIT)或药物诱导性血小板减少症(DITP)。这些抗体通常靶向结合血小板表面糖蛋白(GPs)(见表1)[7-9],多数情况下血小板数量显著减少,严重时血小板计数常常<20×109/L。除HIT外,血小板<10-20×109/L时,ITP与DITP的患者临床症状主要表现为皮下与粘膜出血。

ITP

ITP既往称为特发性血小板减少性紫癜,是一种自身免疫性疾病,以单独的血小板减少(<100×109/L)伴出血倾向为临床表现。ITP的诊断需要排除引起血小板减少的继发性疾病才能确诊。相反,如存在继发性自身免疫疾病与感染,如HCV与HIV,则称为继发性ITP[10,11]。

ITP的病理生理机制

目前认为,ITP的PLT减少是由于循环中PLT清除加快与骨髓中PLT生成受抑所致[12],其主要机制为抗血小板自身抗体(AAbs)诱导的Fc依赖与非依赖性吞噬作用、补体激活或细胞毒性T淋巴细胞的直接细胞裂解作用[13-15],而骨髓中PLT生成受抑则是AAbs的旁路效应,即抑制PLT生成过程,这也是ITP发病的病理生理机制[16]。

ITP的临床过程

ITP的发病与临床病程与年龄有关[17]。据估计,ITP年发病率为成年人每100,000中约1.6-3.9人发病,而儿童为约1.9-6.4人发病[18-20]。儿童ITP中严重出血的情况罕见,大多数可自然缓解,但近年来儿童ITP随着年龄增加转化为慢性的风险亦增高,且慢性期的高峰年龄段多为青少年[10,21]。

相反,成年人ITP则多为慢性期,伴有高出血风险。严重出血的预测因素包括性别、并发症与年龄>60岁[22]。

ITP的诊断

尽管临床上有不同版本的ITP指南,但ITP的诊断对内科医生来说仍具有挑战性[10,23]。事实上,临床报道少部分ITP误诊正是由于缺乏敏感性与特异性的诊断指标,从而导致患者接受了不恰当的治疗[24]。临床可疑ITP的诊断方法应基于患者的病史、体征及外周血计数综合考虑。而且,镜下观察外周血涂片十分必要,有助于排除假性血小板减少症、遗传性血小板减少症以及其他特异性改变如微血管病性溶血(即血栓性血小板减少性紫癜中的红细胞碎片)[23]。

通常ITP患者的平均血小板体积(MPV)是明显增高的。但是,ITP患者人群异质性很大,可见约40%的血小板出现体积增大。如果大体积血小板的出现超过60%或出现巨大的血小板(相当于红细胞体积的一半),则应考虑遗传性巨血小板减少症。骨髓检查并非必须,且对ITP诊断帮助不大,但如果出现不典型表现如难以解释的贫血、淋巴结或脾肿大等情况时,则必须进行骨髓检查以排除其他原因所致的血小板减少。

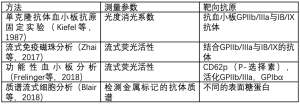

血小板抗体检测的应用,目前仍有争议,且只在小部分的指南中推荐使用[23,25]。需要注意的是,2017年发现抗血小板自身抗体(AAbs)会导致利妥昔治疗无效,因此有必要进行准确的抗血小板自身抗体检测以判断利妥昔疗效[26]。检测这种抗体通常应用单克隆抗体特异性血小板抗原固定术(MAIP)或流式细胞仪检测(见表2)。目前正在开展的标志物检测如CD61(P-选择素)的表达与质谱流式细胞技术的应用,在ITP的诊断和个体化治疗方面具有很大前景(见表2)[27-32]。

Full table

ITP的治疗

由于ITP的症状与病理生理机制各不相同,因此ITP需要进行个体化治疗[33]。治疗的目标主要是降低严重出血的风险与提高PLT数量[10,34-36]。

急性ITP的一线治疗是糖皮质激素免疫球蛋白(IVIGs)与抗D免疫球蛋白。尽管标准的糖皮质激素(如强的松)在ITP初始治疗中非常重要,但由于这类药物具有不良反应、病人依从性差,及起效慢等特点,临床应用受到限制。目前,仅有少数报道发现大剂量地塞米松的疗效优于标准的强的松治疗[37]。因此,仍有待于进一步临床研究探讨大剂量地塞米松在ITP中的不良反应与远期疗效。虽然,一线应用IVIGs治疗的疗效已被临床证实,但是抗D免疫球蛋白的疗效并不一致,目前仅用于表达RhD抗原且未行脾切除的ITP患者。关于抗D免疫球蛋白的具体作用机制尚待进一步研究[38]。

ITP的二线治疗包括脾切除与利妥昔单抗。然而,脾切除治疗ITP的价值仍有争议,因为有可替代的方法如促血小板生成素受体激动剂(TPO-RAs)[39],而且证据显示利妥昔单抗治疗难治/复发性ITP患者疗效更好。利妥昔单抗为人源化的CD20单抗,可清除外周血B淋巴细胞与减少血液循环中的AAbs,因此可提升血小板数量(>50×109/L),对ITP患者具有持续疗效[40]。对于难治/复发性ITP,利妥昔单抗联合糖皮质激素的治疗方法具有很好的前景[41]。因此,很有必要继续探讨利妥昔单抗联合其他药物的治疗方法以减少高不良反应的发生[42]。

目前已发布的ITP治疗指南中,TPO-RAs是一种新型ITP治疗药物。由于缺乏TPO-RA安全性、远期疗效与不良反应的临床数据,TPO-RAs被列为三线替代治疗药物[10]。目前,美国食品与药品管理局(FDA)批准了两款TPO-RA药物上市(即罗米司亭与艾曲波帕),二者具有较高的近期疗效与远期疗效,已被推荐为二线治疗药物[43,44]。而且,在伴有重症ITP的危重患者中,由于TPO-RAs联合糖皮质激素和IVIGs等一线药物具有很好的疗效,这种联合方案得到逐步推广应用[45]。

DITP

临床发现超过300种药物可诱发DITP。一项荟萃分析显示,导致DITP最常见的药物包括:奎宁、奎尼丁、甲氧苄氨嘧啶/磺胺甲恶唑、万古霉素、青霉素、奥沙利铂、苏拉明与GPⅡb/Ⅲa抑制药如阿昔单抗、替罗非班与依替巴肽[46]。

DITP的病理生理

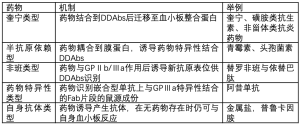

关于DITP的发病机制,目前有以下几种(见表3):(I)奎宁类型的DDAbs:典型的药物依赖抗体(DDAbs),可与PLT紧密结合,但只发生于敏感药物中且多数结合GPⅡb/Ⅲa与GPⅠb//Ⅸ等蛋白。新近研究发现:一种包含奎宁与重修饰抗体的互补位,即DDAbs的补体决定区(CDRs)在识别抗体的靶抗原给位中起关键作用[49];(II)半抗原依赖的DDAbs:分子量<5,000道尔顿的小分子药物(如青霉素)需要与大分子的载体蛋白共价结合(多数为GPⅡb/Ⅲa),诱导产生药物特异性抗体,从而结合小分子药物而不是血小板糖蛋白;(III)Fiban类型的DDAbs:主要见于GPⅡb/Ⅲa抑制药替罗非班与依替巴肽等药物。这些药物可诱导蛋白质结构发生构象改变,从而引发针对血小板的免疫反应;(IV)药物特异性DDAbs:通常见于应用含有小鼠蛋白成份的药物,如鼠-人嵌合型阿昔单抗,其Fab片段可特异性识别GPⅢa,以防止血小板聚集,但同时也可产生药物特异性DDAbs;(V)自身抗体类型:这种抗体在药物(特别是金属类药物)作用以后发生,但药物存在并非抗体与血小板结合所需。尽管DITP的免疫反应被认为具有药物特异性,但近期报道显示,一例患者应用奥沙利铂治疗后产生了多种其他药物的特异性DDAb[50]。

Full table

ITP的临床过程

DITP是一种致命性临床综合征,具有高出血风险。在报道的247例DITP患者中,严重与致命性出血的发生率分别为9%与0.8%[47]。出血症状一般在药物初次应用后1-2周时间出现,血小板的中位最低值<20×109/L。特殊的个例见于GPⅡb/Ⅲa拮抗药诱导的血小板减少症,由于机体存在天然抗体,出血症状最早可在药物应用数小时内发生。

DITP的诊断

诊断DITP的关键在于临床医生的高度认知与对病人既往治疗药物的密切随访,以发现致病性的药物。目前,以下五个临床标准有助于临床诊断DITP[46]:(I)可疑药物应用于血小板减少症出现之前;(II)中断可疑药物治疗后,血小板减少可完全恢复与维持正常水平;(III)在血小板减少发生前,可疑药物为唯一应用药物;或者中断可疑药物后,其他药物继续应用或再次应用,血小板保持正常数量;(IV)排除其他导致血小板减少的药物存在;(V)再次应用可疑药物,血小板减少再次发生。

由于DITP常见于住院患者,需要接受多种治疗且具有引起血小板减少的并发症,临床上很难鉴定出唯一的可疑药物。因此,多数学者认为需要再次进行药物临床验证或DDAbs的体外诊断。目前已有几种实验室方法可检测药物或其代谢产物存在时与血小板结合的抗体。检测方法需要具有药物依赖性、免疫球蛋白结合性与血小板特异性,理论上应该能在各个实验室重复结果。最近,止血与血栓国际学会推荐了DITP的实验室检测方法,其中还提供了提高特异性与敏感性的方法指南[51]。

可疑DITP的治疗

DITP的治疗必须停止应用违规药物。血小板计数通常在4-5个药物或代谢产物的半衰期后才开始恢复。对于重度血小板减少或高出血风险患者,尽管仅基于一些个案报道临床推荐,但可选择大剂量IVIGs治疗[48,52]。由于这类患者血浆中存在药物或代谢产物,血小板输注通常无效。

肝素诱导血小板减少症(HITⅡ型)

HIT是一种普通肝素或低分子肝素应用之后出现的血栓前状态[53]。

HIT的病理生理

接受肝素的许多患者体内易形成高免疫性的多分子复合物(包括带负电荷的聚阴离子和阳离子蛋白-血小板因子4(PF4)),进一步导致抗血小板抗体形成。尽管针对PF4/肝素的免疫发生率很高,但是仅有小部分患者发生HIT。 事实上,仅少数抗PF4/肝素的IgG抗体可与血小板表面的Fc受体发生交叉反应,导致血小板活化,释放血小板颗粒、形成血小板微颗粒、凝血酶生成,最后诱导血小板聚集[53]。内皮细胞与单核细胞活化产生的组织因子也与HIT的发生有关[54]。总之,在缺乏相应的抗凝物质时,上述过程促使了HIT高凝状态与血栓形成。

HIT的临床表现

HIT患者临床表现各异,最主要的表现为肝素应用后的第5-14天出现血小板计数减少>50%。对于既往30天内接受过肝素治疗的免疫前状态患者,有时在肝素应用1小时内即发生血小板下降,称为快速突发性HIT。大多数队列研究显示:HIT的中位血小板最低值在[50-80]×109/L,如合并弥漫性血管内凝血(DIC)时血小板可低至20×109/L以下。

除了血小板减少外,HIT还可发生血栓形成的严重并发症,进一步增加疾病的发病率和死亡率。约50%未经治疗的急性HIT患者发生了新的血栓并发症,其中深静脉血栓(DVT)是最常见的并发症,合并肺栓塞可有可无。在HIT患者中,动脉血栓发生率明显低于静脉血栓,主要见于下肢动脉、脑动脉、冠状动脉、肠系膜动脉与肱动脉等动脉血管[53]。由于重度的HIT相关性DIC引发的微血栓形成与致命的肢体缺血,在未接受华法林治疗的患者中极为罕见。其他罕见的并发症还包括肝素注射部位的皮肤坏死与肾上腺出血性坏死。

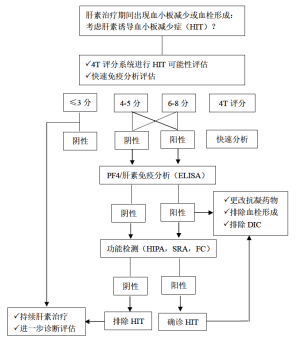

可疑HIT的治疗

对于临床高度可疑的HIT患者,必须停止所有的肝素治疗,更换应用其他非肝素抗凝药物以预防新的血栓并发症。但是,替代的抗凝血药物很少应用在非HIT患者,而且多数内科医生应用这类药物的经验较少,从而导致出血与血栓发生风险相对较高。因此,临床医生一定要对于这类罕见的HIT患者进行鉴别诊断。

鉴别HIT的高危人群

目前,有一些评分系统用以鉴别HIT的高危人群。其中,应用最广泛的评分系统为HIT的4个典型临床特征评分(4Ts评分):(I)血小板减少;(II)血小板减少的开始时间;(III)血栓形成或其他临床后遗症;(IV)其他引起血小板减少的原因[55]。4分以下的阴性预测率高达99.8%,但中或高分的阳性预测率并不高,分别为14%与64%[56]。其他评分系统如HIT专家预测评分与Lillo-Le Louet评分,还需要前瞻性研究进一步验证,才能应用于HIT的临床诊断。

HIT的实验室检查

检测 HIT有两种方法,即血小板活化的功能分析与PF4依赖的免疫分析[57,58]。只有功能分析才能检测到血小板活化的抗体。尽管新近发现全血阻抗分析法可检测血小板活化抗体[59],但HIT检测方法的金标准仍是血小板洗脱的方法,如血小板诱导的血小板活化试验(HIPA)与5-羟色胺释放试验(SRA)(见图1)[61,62]。功能试验在检测临床相关HIT抗体具有高度敏感性与特异性。增加外源性PF4试验,可提高SRA方法的准确性[63]。尽管上述两种功能试验被确立为诊断HIT的金标准,但由于这两种方法检测中需要健康的血小板供者,且限少数实验室能实施,因此尚难以被广泛应用。最近发现流式细胞仪可检测 PLT活化抗体[64]。有文献报道,在对两例HIT患者密切随访中,发现在SRA检测抗体阳性之前,应用PF4依赖的P选择素表达试验即可检测到致病性抗体存在[65]。

相比功能试验,酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)与颗粒免疫试验更容易检测抗PF4/肝素抗体。

ELISAs在排除HIT的阴性预测率更高,但特异性并不高,仅为40-80%[57]。有几种方法可增加ELISAs的诊断特异性,包括排除性检测抗PF4/肝素的IgG抗体,考虑检测OD值的强度与进行抑制验证检测。然而,最近一项荟萃分析发现,相比多特异性ELISAs方法,IgG特异性方法在提高免疫分析特异性方面并不具有更好的优势[66]。

颗粒免疫试验不仅操作方便,还可通过离心后行颗粒凝胶免疫试验或流式技术清晰识别结果。这些试验最主要的优势是报告结果很快,且阴性预测率很高[67]。新近研发了自动颗粒免疫试验的新技术。一篇荟萃分析发现:快速免疫试验在HIT中的阴性预测率很高,特别是可排除可能性低或中等的HIT患者[68]。

可疑HIT患者的抗凝治疗

对于临床高度怀疑HIT的患者,应立即给予非肝素类的抗凝药治疗,而不能等待实验室检查结果以确定或排除HIT诊断。目前,有不同的抗凝药用于治疗HIT患者。

活化因子X抑制药

对于HIT患者,在预防新出现、进行性、复发性血栓并发症(包括血栓性死亡)或截肢手术方面,达那肝素具有良好的疗效[69],主要原因如下:(I)达那肝素与HIT的抗血小板抗体交叉反应小;(II)达那肝素可抑制抗血小板抗体诱发的血小板活化,而不是在血小板表面形成PF4/肝素复合物;(III)破坏PF4/肝素复合物形成。

在HIT治疗中,磺达肝癸钠应用日益广泛[70],其在肝素依赖性血小板活化抗体诱发的动脉血栓患者中也具有很好的安全性[71]。

凝血酶抑制药

阿加曲班为合成的凝血酶抑制药,通过可逆性结合凝血酶活化部位发挥抗凝作用,它可抑制游离和血栓结合状态的凝血酶。两项多中心临床试验显示:与对照组相比,阿加曲班显著减少HIT患者的死亡、截肢与血栓发生[72]。

比伐卢定是另一种合成的凝血酶抑制药,主要应用于非HIT合并冠脉疾病的患者,包括急性冠脉综合征与需要冠脉介入治疗患者[73]。

口服抗凝药物(DOAC)

利伐沙班,阿哌沙班与艾多沙班可直接抑制活化因子X,而达比加群则是直接的凝血酶抑制药。DOAC不仅安全性好,且疗效确切,并不引起新的血栓形成。但是,在急性HIT患者中,应用以上药物的经验有限,关于它们的临床优势也并无定论。特别重要的是,这些药物的谷浓度并不足以预防HIT患者血栓形成。

IVIG

大剂量IVIG被证明可抑制HIT抗体介导的血小板活化。累计的临床报道显示:标准治疗无效的血小板减少患者可受益于IVIG治疗[74]。

HIT预防

前述提到,包含阴性带电荷离子与阳离子蛋白PF4的多分子复合物的形成,进一步促进了接受肝素治疗患者的抗血小板抗体形成。与普通肝素相比,预防性应用低分子肝素可降低HIT发生风险,降低至10倍之多。最近一项研究显示:以低分子肝素代替普通肝素的策略,极大减少了HIT的发生风险[75]。

鱼精蛋白/肝素诱导的血小板减少症(PHIT)

在心脏术后患者中,鱼精蛋白与肝素形成的多分子复合物可刺激机体免疫反应高发。这些抗鱼精蛋白/肝素的IgG抗体是通过结合FcγⅡA受体发挥活化血小板功能。

PHIT诊断

应用ELISAs试验可检测抗鱼精蛋白/肝素抗体。与单用鱼精蛋白相比,肝素可提高抗鱼精蛋白抗体的结合力[76,77]。鱼精蛋白在结合肝素后即发生构象改变,从而促使抗鱼精蛋白/肝素抗体更易结合到鱼精蛋白的新抗原表位上[78,79]。应用SRA试验与HIPA试验可体外检测抗鱼精蛋白/肝素抗体的活化血小板特性[79-83]。

抗鱼精蛋白/肝素抗体的临床表现

有报道称,抗鱼精蛋白/肝素抗体(IgG/A/M)并不影响术后血小板数量[80,82]。但是,术前存在的抗鱼精蛋白/肝素抗体与心脏术后血小板数量减少和鱼精蛋白中和需求增加密切相关[79,83]。此外,血栓形成并发症也出现在抗鱼精蛋白/肝素抗体的患者中[76,84]。目前,关于PHIT的治疗,尚无足够的经验。最近的病例系列报道了使用阿加曲班治疗的4例PHIT患者,血小板数量很快恢复,还观察到一些不良反应[84]。

结论

本文中提出血小板数量是判断血小板生成与存活的敏感指标。由于血小板数量减少可作为严重基础性疾病的最初表现,因此AITP患者需要临床高度重视与进行详细诊疗。深入了解AITP患者的免疫发生机制,对于改善患者的生活质量具有重要的意义。进一步理解这些机制,不仅有助于提出新的治疗策略,而且为预防感染与自身免疫疾病继发的血小板减少提供新的策略。

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Bosher and Karina Althaus for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by a grant from the German Research Society and the German Red Cross.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Sentot Santoso) for the series “Platelet Immunology” published in Annals of Blood. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The series “Platelet Immunology” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. T Bakchoul reports receiving honorarium for a scientific talk from Aspen Germany, CSL Behring, Stago gGmbH German, and research Grants from the German Society of Research, the German Society for Transfusion Medicine and German Red Cross. J Zlamal has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the manuscript and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- McMahon CM, Cuker A. Hospital-acquired thrombocytopenia. Hosp Pract (1995) 2014;42:142-52. [PubMed]

- Modderman PW, Admiraal LG, Sonnenberg A, et al. Glycoproteins V and Ib-IX form a noncovalent complex in the platelet membrane. J Biol Chem 1992;267:364-9. [PubMed]

- Kovacsovics TJ, Hartwig JH. Thrombin-induced GPIb-IX centralization on the platelet surface requires actin assembly and myosin II activation. Blood 1996;87:618-29. [PubMed]

- Enayat S, Ravanbod S, Rassoulzadegan M, et al. A novel D235Y mutation in the GP1BA gene enhances platelet interaction with von Willebrand factor in an Iranian family with platelet-type von Willebrand disease. Thromb Haemost 2012;108:946-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtis BR, McFarland JG. Human platelet antigens - 2013. Vox Sang 2014;106:93-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michelson AD. Platelets. 3rd edition. Academic Press, 2012:195-248.

- Cines DB, Cuker A, Semple JW. Pathogenesis of immune thrombocytopenia. Presse Med 2014;43:e49-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Visentin GP, Ford SE, Scott JP, et al. Antibodies from patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia/thrombosis are specific for platelet factor 4 complexed with heparin or bound to endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 1994;93:81-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtis BR. Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia: incidence, clinical features, laboratory testing, and pathogenic mechanisms. Immunohematology 2014;30:55-65. [PubMed]

- Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2011;117:4190-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodeghiero F, Ruggeri M. ITP and international guidelines: what do we know, what do we need? Presse Med 2014;43:e61-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cines DB, Liebman HA. The immune thrombocytopenia syndrome: a disorder of diverse pathogenesis and clinical presentation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009;23:1155-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakchoul T, Walek K, Krautwurst A, et al. Glycosylation of autoantibodies: insights into the mechanisms of immune thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost 2013;110:1259-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMillan R. The pathogenesis of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin Hematol 2007;44:S3-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMillan R, Nugent D. The effect of antiplatelet autoantibodies on megakaryocytopoiesis. Int J Hematol 2005;81:94-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ballem PJ, Segal GM, Stratton JR, et al. Mechanisms of thrombocytopenia in chronic autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. Evidence of both impaired platelet production and increased platelet clearance. J Clin Invest 1987;80:33-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kühne T, Buchanan GR, Zimmerman S, et al. A prospective comparative study of 2540 infants and children with newly diagnosed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) from the Intercontinental Childhood ITP Study Group. J Pediatr 2003;143:605-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurata Y, Fujimura K, Kuwana M, et al. Epidemiology of primary immune thrombocytopenia in children and adults in Japan: a population-based study and literature review. Int J Hematol 2011;93:329-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terrell DR, Beebe LA, Vesely SK, et al. The incidence of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children and adults: A critical review of published reports. Am J Hematol 2010;85:174-80. [PubMed]

- Moulis G, Palmaro A, Montastruc JL, et al. Epidemiology of incident immune thrombocytopenia: a nationwide population-based study in France. Blood 2014;124:3308-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bennett CM, Neunert C, Grace RF, et al. Predictors of remission in children with newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia: Data from the Intercontinental Cooperative ITP Study Group Registry II participants. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018;65: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fogarty PF. Chronic immune thrombocytopenia in adults: epidemiology and clinical presentation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009;23:1213-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matzdorff A, Meyer O, Ostermann H, et al. Immunthrombozytopenie - aktuelle Diagnostik und Therapie: Empfehlungen einer gemeinsamen Arbeitsgruppe der DGHO, OGHO, SGH, GPOH und DGTI. Oncol Res Treat 2018;41:5-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold DM, Nazy I, Clare R, et al. Misdiagnosis of primary immune thrombocytopenia and frequency of bleeding: lessons from the McMaster ITP Registry. Blood Adv 2017;1:2414-20. [PubMed]

- McMillan R, Wang L, Tani P. Prospective evaluation of the immunobead assay for the diagnosis of adult chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). J Thromb Haemost 2003;1:485-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold DM, Vrbensky JR, Karim N, et al. The effect of rituximab on anti-platelet autoantibody levels in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol 2017;178:302-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basu SS, Deutsch EC, Schmaier AA, et al. Human platelets as a platform to monitor metabolic biomarkers using stable isotopes and LC-MS. Bioanalysis 2013;5:3009-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frelinger AL 3rd, Grace RF, Gerrits AJ, et al. Platelet Function in ITP, Independent of Platelet Count, Is Consistent Over Time and Is Associated with Both Current and Subsequent Bleeding Severity. Thromb Haemost 2018;118:143-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhai J, Ding M, Yang T, et al. Flow cytometric immunobead assay for quantitative detection of platelet autoantibodies in immune thrombocytopenia patients. J Transl Med 2017;15:214. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porcelijn L, Huiskes E, Oldert G, et al. Detection of platelet autoantibodies to identify immune thrombocytopenia: state of the art. Br J Haematol 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kiefel V, Santoso S, Weisheit M, et al. Monoclonal antibody--specific immobilization of platelet antigens (MAIPA): a new tool for the identification of platelet-reactive antibodies. Blood 1987;70:1722-6. [PubMed]

- Blair TA, Michelson AD, Frelinger AL 3rd. Mass Cytometry Reveals Distinct Platelet Subtypes in Healthy Subjects and Novel Alterations in Surface Glycoproteins in Glanzmann Thrombasthenia. Sci Rep 2018;8:10300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lozano ML, Revilla N, Gonzalez-Lopez TJ, et al. Real-life management of primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) in adult patients and adherence to practice guidelines. Ann Hematol 2016;95:1089-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Provan D, Newland AC. Current Management of Primary Immune Thrombocytopenia. Adv Ther 2015;32:875-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neunert CE. Management of newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia: can we change outcomes? Blood Adv 2017;1:2295-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matzdorff A, Giagounidis A, Greinacher A, et al. Diagnosis and therapy of autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Recommendations of a joint Expert Group of DGHO, DGTI, DTH. Onkologie 2010;33:2-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Din B, Wang X, Shi Y, et al. Long-term effect of high-dose dexamethasone with or without low-dose dexamethasone maintenance in untreated immune thrombocytopenia. Acta Haematol 2015;133:124-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Depré F, Aboud N, Mayer B, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of old and new drugs used in the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia: Results from a long-term observation in clinical practice. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198184 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cuker A, Cines DB, Neunert CE. Controversies in the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia. Curr Opin Hematol 2016;23:479-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel VL, Mahevas M, Lee SY, et al. Outcomes 5 years after response to rituximab therapy in children and adults with immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2012;119:5989-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gudbrandsdottir S, Birgens HS, Frederiksen H, et al. Rituximab and dexamethasone vs dexamethasone monotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2013;121:1976-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shoukat BA, Ali O, Kumar D, et al. Hypogammaglobulinemia Observed One Year after Rituximab Treatment for Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura. Case Rep Med 2018;2018:2096186 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuter DJ, Macahilig C, Grotzinger KM, et al. Treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) switched to eltrombopag or romiplostim. Int J Hematol 2015;101:255-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong RSM, Saleh MN, Khelif A, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term treatment of chronic/persistent ITP with eltrombopag: final results of the EXTEND study. Blood 2017;130:2527-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elgebaly AS, Ashal GE, Elfil M, et al. Tolerability and Efficacy of Eltrombopag in Chronic Immune Thrombocytopenia: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2017;23:928-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold DM, Kukaswadia S, Nazi I, et al. A systematic evaluation of laboratory testing for drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost 2013;11:169-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- George JN, Raskob GE, Shah SR, et al. Drug-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review of published case reports. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:886-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold DM, Nazi I, Warkentin TE, et al. Approach to the diagnosis and management of drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Transfus Med Rev 2013;27:137-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu J, Zhu J, Bougie DW, et al. Structural basis for quinine-dependent antibody binding to platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Blood 2015;126:2138-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtis BR, Hsu YS, Podoltsev N, et al. Patients treated with oxaliplatin are at risk for thrombocytopenia caused by multiple drug-dependent antibodies. Blood 2018;131:1486-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold DM, Curtis BR, Bakchoul T, et al. Recommendations for standardization of laboratory testing for drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13:676-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tvito A, Bakchoul T, Rowe JM, et al. Severe and persistent heparin-induced thrombocytopenia despite fondaparinux treatment. Am J Hematol 2015;90:675-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greinacher A. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:252-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kasthuri RS, Glover SL, Jonas W, et al. PF4/heparin-antibody complex induces monocyte tissue factor expression and release of tissue factor positive microparticles by activation of FcgammaRI. Blood 2012;119:5285-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lo GK, Juhl D, Warkentin TE, et al. Evaluation of pretest clinical score (4 T's) for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in two clinical settings. J Thromb Haemost 2006;4:759-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cuker A, Gimotty PA, Crowther MA, et al. Predictive value of the 4Ts scoring system for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood 2012;120:4160-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakchoul T, Zollner H, Greinacher A. Current insights into the laboratory diagnosis of HIT. Int J Lab Hematol 2014;36:296-305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagler M, Bakchoul T. Clinical and laboratory tests for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost 2016;116:823-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morel-Kopp MC, Mullier F, Gkalea V, et al. Heparin-induced multi-electrode aggregometry method for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia testing: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2016;14:2548-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakchoul T, Hinz A. Diagnostik von angeborenen und erworbenen Thrombozyten-Erkrankungen. Haemotherapie 2017;28:4-12.

- Greinacher A, Michels I, Kiefel V, et al. A rapid and sensitive test for diagnosing heparin-associated thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost 1991;66:734-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sheridan D, Carter C, Kelton JG. A diagnostic test for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood 1986;67:27-30. [PubMed]

- Vayne C, Guery EA, Kizlik-Masson C, et al. Beneficial effect of exogenous platelet factor 4 for detecting pathogenic heparin-induced thrombocytopenia antibodies. Br J Haematol 2017;179:811-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan A, Jones CG, Curtis BR, et al. A Novel PF4-Dependent Platelet Activation Assay Identifies Patients Likely to Have Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia/Thrombosis. Chest 2016;150:506-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones CG, Pechauer SM, Curtis BR, et al. A Platelet Factor 4-Dependent Platelet Activation Assay Facilitates Early Detection of Pathogenic Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia Antibodies. Chest 2017;152:e77-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagler M, Bachmann LM, Ten Cate H, et al. Diagnostic value of immunoassays for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood 2016;127:546-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Linkins LA, Bates SM, Lee AY, et al. Combination of 4Ts score and PF4/H-PaGIA for diagnosis and management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: prospective cohort study. Blood 2015;126:597-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun L, Gimotty PA, Lakshmanan S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of rapid immunoassays for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost 2016;115:1044-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lubenow N, Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, et al. Results of a systematic evaluation of treatment outcomes for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients receiving danaparoid, ancrod, and/or coumarin explain the rapid shift in clinical practice during the 1990s. Thromb Res 2006;117:507-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schindewolf M, Steindl J, Beyer-Westendorf J, et al. Frequent off-label use of fondaparinux in patients with suspected acute heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)--findings from the GerHIT multi-centre registry study. Thromb Res 2014;134:29-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warkentin TE, Davidson BL, Buller HR, et al. Prevalence and risk of preexisting heparin-induced thrombocytopenia antibodies in patients with acute VTE. Chest 2011;140:366-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewis BE, Wallis DE, Leya F, et al. Argatroban anticoagulation in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1849-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, Koster A. Bivalirudin. Thromb Haemost 2008;99:830-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan A, Jones CG, Pechauer SM, et al. IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Chest 2017;152:478-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGowan KE, Makari J, Diamantouros A, et al. Reducing the hospital burden of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: impact of an avoid-heparin program. Blood 2016;127:1954-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Panzer S, Schiferer A, Steinlechner B, et al. Serological features of antibodies to protamine inducing thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:249-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee GM, Joglekar M, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Serologic characterization of anti-protamine/heparin and anti-PF4/heparin antibodies. Blood Adv 2017;1:644-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chudasama SL, Espinasse B, Hwang F, et al. Heparin modifies the immunogenicity of positively charged proteins. Blood 2010;116:6046-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakchoul T, Zollner H, Amiral J, et al. Anti-protamine-heparin antibodies: incidence, clinical relevance, and pathogenesis. Blood 2013;121:2821-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pouplard C, Leroux D, Rollin J, et al. Incidence of antibodies to protamine sulfate/heparin complexes incardiac surgery patients and impact on platelet activation and clinical outcome. Thromb Haemost 2013;109:1141-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singla A, Sullivan MJ, Lee G, et al. Protamine-induced immune thrombocytopenia. Transfusion 2013;53:2158-63. [PubMed]

- Lee GM, Welsby IJ, Phillips-Bute B, et al. High incidence of antibodies to protamine and protamine/heparin complexes in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Blood 2013;121:2828-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grieshaber P, Bakchoul T, Wilhelm J, et al. Platelet-activating protamine-heparin-antibodies lead to higher protamine demand in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;150:967-73.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wadowski PP, Felli A, Schiferer A, et al. Argatroban in Thrombocytopenic Patients Sensitized to Circulating Protamine-Heparin Complexes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:1779-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

丁江华

医学博士,副主任医师,副教授,硕士生导师。现任九江学院附属医院血液肿瘤科副主任。2015年荣获江西省优秀博士学位论文奖。先后承担与参与多项国家、省、市级科研课题。(更新时间:2021/8/12)

蒋祺

河南大学医学院免疫学硕士研究生学历,输血技术中级职称,开封市检验协会委员,2015年至今任核酸实验室主任。长期从事血液分子生物学研究,研究生期间参与2项国家自然科学基金研究工作。2016年,在中国医师协会和输血医师分会联合举办的“迎接新常态,勇做输血领军人”全国人才选拔活动中,入选“全国输血医学人才库”。在国家级刊物中发表多篇学术论文。(更新时间:2021/8/26)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Zlamal J, Bakchoul T. Acquired immune thrombocytopenia: an update on pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Ann Blood 2018;3:45.