Immune thrombocytopenia: the patient’s perspective

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a rare heterogeneous autoimmune bleeding disorder that causes a lower than normal circulating platelet count from both decreased platelet production and accelerated platelet destruction. This is the result of autoantibody and cell-mediated immune responses targeting platelets for destruction (1). Some ITP patients are fortunate to see their disorder resolve with or without the use of medical intervention (2,3). For most patients, living with ITP creates life-long challenges and impacts how they feel and function (3).

PDSA was patient-founded in 1998 to empower individuals with Immune Thrombocytopenia and other platelet disorders through education, advocacy, research, and support. Today, the organization is a powerful force serving and unifying the global ITP community of patients, practitioners, caregivers, advocates and key disease stakeholders.

In this review, we aim to illustrate the patient perspective regarding their perceived unmet needs and the physical and emotional burden of disease in an attempt to highlight areas where healthcare providers treating ITP can enhance their current approach to managing ITP patients. This will be accomplished through a compilation of experiences with ITP collected from work the Platelet Disorder Support Association (PDSA) has done over the years in various capacities, including through the ITP Natural History Study Patient Registry and the externally led Patient-Focused Drug Development (EL-PFDD) meeting (4). Formal results from the ITP Natural History Study Patient Registry and the EL-PFDD meeting have been published previously (4-7) and will be summarized further here.

In 2017, PDSA with assistance from the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), launched the ITP Natural History Study Patient Registry to better understand ITP patient characteristics, their disease, disease management, and their quality of life to help to establish patient-reported outcomes and leverage ITP patients (and caregivers) as active participants in research. Currently, the ITP Natural History Study Patient Registry has 1,110 patients enrolled to date, with 324 adult ITP patients participating in two adult-specific QoL surveys and 44 caregivers participating in one child-specific QoL survey on behalf of their child. To date, most registry participants are from the USA (85%), female (76%), adult (between the ages of 18–60 years), who are insured (93%), and have received treatment for their ITP (91%) at some point. The QoL based questions within the registry were created using NIH PROMIS standards (8), and included the following measures in the adult surveys: GRDR:ORDR Model Data, PROMIS SF v1.1 Global Health, PROMIS-57 Profile v2.0 (Investigator version), PROMIS-item bank v2.0 Emotional Support, Short form 8a; and the following for the pediatric survey: the PROMIS Ped-49 Profile v1.1 (Investigator version), and PhenX Toolkit Protocol 220702.

The EL-PFDD meeting, hosted by PDSA on July 26, 2019, integrated patient insights, needs, and priorities into drug development and evaluation and gave the ITP community an opportunity to directly inform the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) about the realities of living with ITP, the overall QoL of an ITP patient, and what patients need to ultimately achieve the best health outcomes.

Background

While all age groups are susceptible to the development of ITP (4,9), the expected natural history of the disorder varies depending on the age at which the ITP diagnosis is made. Most adults who are diagnosed with ITP will develop chronic ITP (80%), whereas the majority of children with ITP will see their ITP resolve within the first year (80%). As a result, adult and pediatric cases of ITP are often managed differently (9). Regardless of age or disease phase, the majority of ITP patients do not experience significant bleeding events (9-11). Patients with ITP may exhibit symptoms of petechiae, purpura, and gastrointestinal and/or urinary mucosal tract bleeding (12). The greatest concern with ITP is the risk of significant internal bleeding, such as an intracranial hemorrhage. Other clinically significant concerns include complications from internal bleeding and an elevated risk of thrombosis and thromboembolism (13). Management depends on severity of symptoms, platelet count, age, lifestyle, response to therapy and side effects, the presence of other concomitant medical issues that affect the risk of bleeding, quality of life, financial barriers, and personal preferences of both the patient and the doctor.

Patients with ITP face many challenges. Actual disease burdens and perceived disease risks both influence the physical, emotional, and social health of patients and families with ITP impacting negatively their overall health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (14-25). ITP is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality affecting all facets of life. Due to the heterogeneity of ITP’s pathophysiology and disease course, living with ITP can be difficult and unpredictable despite several available therapies, and treatment strategies to influence disease course (26). ITP patients experience a range of physical and emotional consequences as they monitor their platelet count, balance treatment side effects, and manage the fear of bleeding and frequent reality of relapse (27).

Quality of life

While many physicians focus primarily on low platelet counts as the best approach to manage their patients and avoid life-threatening bleeds, for many patients the platelet count is the last thing they are concerned with. In fact, patient respondents to the ITP World Impact Survey (I-WISh) stated that increasing energy levels is one of the top treatment goals (28), alongside finding a medication that reduces fatigue, anxiety around platelet count, and bruising (18,22,24). Patients with ITP want treatments they can afford, that last, and don’t cause additional health concerns as a side-effect or compromise their emotional well-being (27,29,30). Most patients focus on the ways ITP has negatively touched their lives, affecting how they feel and function. Despite an overwhelming number of ITP patients saying that they are in good health, when asked specifically, a very high proportion report ITP negatively impacts their energy levels, their ability to work or study, and their emotional well-being (22,23,25,28-32). In fact, while most individuals with ITP will only experience mild bleeding events usually limited to petechiae and bruising (11), the fear of ITP worsening and the fear of a more serious, life-threatening bleed looms over patients interfering with their family, social life, and work life particularly with energy and productivity, career advancement, and requiring more time off (6,14,22,33).

During the EL-PFDD meeting, one of the patient panelists discussed what health care providers should know when treating ITP and stated, “ITP does not just affect the blood, it also affects you physically and emotionally.” Many patients and caregivers expressed that they or their loved ones have had opportunities taken from them to participate in activities they love or pursue things they are passionate about (Videos 1-3). A number of individuals struggle to complete daily tasks and activities due to fatigue associated with their ITP. For instance, work attendance, work productivity, and chores have been reported to be impacted by just over half of all ITP patients (22,33). Respondents to I-WISh stated that overall, 84% experienced reduced energy levels and 77% stated ITP reduced their capacity to exercise, 75% of ITP patients reported they were unable to perform daily tasks, and 70% reported their social life was impaired due to their ITP (22). This reveals just how debilitating the disease is, and how no aspect of life is free from its reach.

Physical function

Fatigue

Fatigue is the most common symptom reported by patients with ITP regardless of age (7,32,34). In many cases, it is the most severely debilitating symptom reported by patients living with ITP (17,27). This is also supported by research from within the autoimmune disease community, where fatigue rates are high, revealing 98% of patients with an autoimmune disease suffer from fatigue, and almost 60% reporting their fatigue levels are the most debilitating symptoms of their disorder (35). Unfortunately, many providers still undervalue the impact fatigue has on patients living with ITP (17,18,24,30).

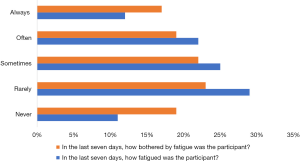

A high incidence of fatigue is also seen among adult participants in the registry. In our registry, when adult participants were asked to reflect on their fatigue levels over the last 7 days, 89% reported they were fatigued, and 81% reported they were bothered by their fatigue (Figure 1) (6). A panellist at the EL-PFDD meeting shared his experience with ITP as a young adult and described his fatigue as ‘unbearable’ and that his fatigue and depression caused by ITP ruined many events in his life that were meant to be positive and fun experiences. He expressed, “[ITP] drained me of my happiness and my ability to enjoy life. I often had to pretend I was happy to make my family happy and to make things seem ok when they weren’t. I believed that eventually I would just become… a ghost of who I was just watching life around me, but not living it.” He also went on to share that his fatigue was so debilitating he had to sleep in his car in between his college classes and described his life with ITP as “an endless cycle of misery, pain, and losing who I was” (Video 1).

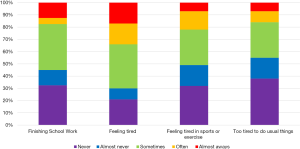

Overall, 79% of caregivers of children with ITP (under 18 years of age) reported within our patient registry that they have seen their child struggle with fatigue as part of their ITP, and within the last seven days, over 60% reported their child has had difficulties completing their schoolwork and engaging in usual activities due to their fatigue (7) (Figure 2).

The exact cause of the fatigue in adult and children with ITP remains a mystery as the incidence of fatigue does not appear in many cases to be related to treatment type, bleeding symptoms or platelet count (14,24,30), however a recent study reported that treatment with second-line therapies did improved fatigue in adolescents and children with ITP (32).

Pain

Pain is not typically reported in the literature as a symptom of ITP. Approximately 15% children are reported to experience pain in the general population, as reported by their parents or caregiver (36). Within our pediatric ITP population, 42% reported they felt pain as part of their ITP. For some ITP patients (9%) this interfered with their ability to finish their schoolwork (7). Sleep was also impacted by pain; in fact, 36% reported difficulties falling asleep in the last 7 days (7) (Figure 3). It is unclear the exact nature or etiology of their pain, if is it treatment related or part of the disease. Future directions should look to see if pain and pain-induced sleep disturbances are also present among adults represented in our database.

Mental health function

Not all symptoms of ITP are visible: this can further frustrate ITP patients as they learn to navigate life with their disorder. One PDSA patient member (Video 1) shared that because his ITP is ‘invisible’ his “friends, even teachers, sometimes think I am pretending to be sick to get out of doing things. But what they don’t understand is the only break I am looking for is a break from ITP”.

In the general population, anxiety disorders affect over 18% annually (37,38). Over 7% of the general population experience clinical depression each year (38).

Anxiety

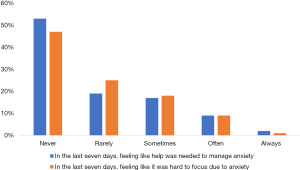

Anxiety is another symptom often reported in both adults and children with ITP (5-7,34). According to our patient registry, almost half of all adult participants reported feeling like they needed help with their anxiety within the past week, and over half reported it was hard to focus on anything because of their anxiety (6) (Figure 4). Caregivers reported their children with ITP felt nervous (56%), worried (76%) and anxious (62%) over what could happen to them within the last week (7).

Many patients have reported they have anxiety over their platelet counts, worsening disease, and even about the possibility they may die (23). Living with ITP means living with unpredictability and a fear of bleeding which negatively impacts the QoL of most ITP patients, particularly if severe or spontaneous bleeding events occur. During the EL-PFDD meeting, a PDSA patient member shared “Predicting platelet levels is a risky business. There have been many times that I planned a vacation thinking my counts were safe and have wound up hemorrhaging out on an airplane due to the combination of my low platelets and the cabin pressure” (Video 1). The unpredictability is frightening. At the EL-PFDD meeting, a live polling session occurred with results revealing that almost half of the participants felt anxiety is one of the top three symptoms that have a significant impact on their life, further demonstrating that ITP goes beyond the physical symptoms and can severely impact patients’ emotional and mental well-being. Anxiety over variable and low platelet counts, restricted lifestyles, fear of the unknown, and treatment side effects can consume a patient’s life.

Depression

One of the more difficult ITP symptoms to treat is also one of the primary causes of disability in the general population (38,39), depression. Depression is often co-morbid with fatigue, and is frequently reported in ITP in both adults and children (5,6,23,24). One PDSA member shared he relapsed with ITP as an adult and this led to such depression he attempted suicide in 2015. Once his ITP diagnosis returned, for ten months he didn’t leave his house because he was afraid, and the depression made him feel ill (Video 2). Depression is also echoed in many ITP patient stories (Videos 1 and 2). Caregivers of children with ITP reported in our ITP Natural History Study Registry that 76% feel generally unhappy, and almost half (46%) experience chronic sadness due to their ITP (7).

In our registry, only 20% of adults with ITP reported their overall QoL to be “poor-fair” (5).

When caregivers were asked to report on their child’s support systems within our patient registry, 83% reported their child often/always felt accepted by their peers, and 80% had friends that helped each other. Just under 70% had friends they felt they could openly talk to about their ITP (7). This is relevant because it shows that while a good support system is in place and overall QoL is good, there are still significant mental health affects attributed directly to ITP.

It is not clear whether depression seen in association with ITP is a result of living with a chronic disease, or whether it is due to the disease itself, or whether it’s a side-effect of treatment, such as with corticosteroids, a common ITP therapy. The effects on mental health from corticosteroids among patients with ITP has been well-documented, including how such effects are often under-appreciated by health care providers (40). For optimal patient care and enhanced clinical practice, it is imperative for hematologists and other ITP providers to listen to their patients who are the experts of living with ITP, to validate their experience and optimize their quality of health care. The following are patient perceived deficiencies in care identified by individuals with ITPs who are PDSA members for the purpose of striving for change and enhanced management.

Unmet patient needs

Communication

- Open and timely communication with ITP providers.

Families want detailed protocols to provide to workplaces and schools with knowledge on what to do regarding limitations and when bleeding happens. A plan that is frequently updated as symptoms change. ITP can be overwhelming for patients and their families and often can lead to isolation. Patients and their families want robust up-to-date information about ITP at the time of their diagnosis and throughout their care. This need has previously been documented among parents of children with complex often rare disorders (41).

Possible solution: Health care providers treating ITP patients should have standardized protocols to provide to workplaces, schools, and ITP families regarding when to seek medical attention, what symptoms to report, and possible restrictions if they apply. Health care providers could consider connecting with the PDSA for patient resources to give to newly diagnosed adults and children with ITP. If ITP management is provided through a specialist within a hospital setting, health care providers could also consider ensuring all providers among the hematology/oncology team manage ITP patients guided by professional practice guidelines to ensure that patient care does not change depending on the provider seen within that same institute, for optimal patient care.

Connection

- Patients and caregivers want to be able to reach their specialist when questions come up or new symptoms appear for reassurance and guidance.

Patients want to be involved in their own management plan and they want to have more of a ‘partnership’ with their ITP providers. Patients want to be included in treatment decisions and they want to be educated on all available treatment options, included those not covered through their own public or private health insurance.

ITP patients often wish for the ability to connect with other families/patients with ITP who understand what it is like to live with their disorder.

Possible solution: ITP patients (or their parent/caregiver) should be provided with a number to call after-hours and during the day if they have any questions or concerns. These calls should be included in the patient’s medical record. Health care providers could also consider referring their ITP patients/families to the PDSA to connect with other individuals and families with ITP, and gain access to PDSA programs and services such as support groups and discussion groups often including an ITP specialist.

Education and patient perceived knowledge deficits

- Patients and caregivers want providers to have current knowledge about ITP and be aware of updated guidelines and how to use them, clinical trials and research, and all available second-line therapies (4,27,42-44).

Often, the discovery of a low platelet count is made by an emergency physician or a family doctor when a patient shows up with unexplained bruising or petechiae. Patients want ITP specialists to educate their colleagues to provide correct information and management recommendations while they wait for a hematologist to become involved.

ITP patients want to be informed of the risks and benefits so they can make an informed choice aligned with their treatment goals. Patients also want to be made aware of resources about their disease and how to connect with others living with their same rare disease (4). This need has also previously been documented among parents of children with complex and often rare disorders (45).

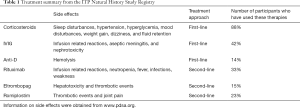

Some patients express their provider is unaware of what treatments are available to ITP patients and when it’s appropriate to suggest their use. This includes not being sure when to consider splenectomy in both adult and pediatric ITP, and the overuse of corticosteroids and other deviations from recommended guidelines (27). While there are newer therapies available for ITP, still many ITP patients report they are receiving corticosteroids for longer durations than necessary (4,46). In our registry more ITP patients (88%) have tried steroids by far more than any other available treatment regime (6) (Table 1). Considered first-line therapy, steroids are less expensive than most other ITP medications, they are readily available and often increase a patients’ platelet count, however this approach does not recognize the long-term burden steroids cause and the impact of daily living. Newer ITP therapies such as thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) have been shown to be effective with fewer side effects, and current guidelines suggest that if used earlier in the course of the disease, there may be better clinical outcomes for patients (43,44). The stories patients share with PDSA of their healthcare providers who over-treat or incorrectly treat ITP patients due to their minimal or outdated knowledge about this rare disease are too common.

Full table

Possible solution: Health care providers treating ITP patients should stay current on research in the field, including updated protocols and best practices. Since ITP is heterogenous and a rare disease, it is essential that health care providers consider using guidelines written by ITP experts when making clinical judgements. They could also consider when new guidelines are developed to hold rounds or present to their colleagues such as pediatricians, family doctors, emergency staff, and inpatient providers.

Enhanced understanding of bleeding risks

- Enhanced understanding is needed on when to modify individual management plans (when to treat and why) and a proper understanding of the ‘watchful waiting’ approach (what is it, and what it isn’t) (47), and what to do when bleeding patterns change (Video 3).

To date, there isn’t a standard way to predict who will develop a critical life-threatening bleed. However, there is substantial guidance published to delineate which ITP patients deserve the opportunity for treatment not only to stop an active bleed, but to prevent a critical/major bleed which is an established therapeutic goal (11,44). Critical bleeds tend to occur more in patients with critically low platelet counts who also have bleeding such as ‘wet’ oral bleeds, recurrent gingival bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, hematuria, and often have a poor or lack of response to steroids (48-54).

Many hematologist-oncologists who take care of patients with ITP may dedicate more time to other diseases perceived as more serious, for example, blood cancers. Therefore, they may not have time to keep up-to-date on how to best manage patients with ITP. This results in limited availability to patients of up-to-date treatments, misuse of certain treatments or persisting with ineffective treatments, or the patient being told that they cannot be successfully treated and left with a very low platelet count, bleeding, and the aforementioned mental and physical symptoms. Similar information from a study in Italy focused on children with ITP found that caregivers wanted more empathy, humanity, and professionalism from ITP providers treating their children (21). While ITP may be ‘benign’ it certainly wreaks havoc to those who live with it, and those who have lost a family member from having ITP.

Patients want their health care providers to know that platelet counts matter, but it should not be the sole driver behind management decisions. Rather, therapy should be based on mitigating bleeding symptoms and improving HRQoL (4,43,44). Patients and caregivers want providers to personalize risks for serious bleeding based on their personal (or their child’s own) clinical history. This would include risk stratification when discussing the probability of an ICH so that ITP patients who’ve experience serious bleeding are not provided with the same exact ICH risk as ITP patients who have minimal bleeding only as mild petechia and bruising. Family members who lost a relative to ITP from an intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) want providers to be vigilant about monitoring their ITP patients for an ICH and other severe bleeding events even though they are a rare complication. This includes being knowledgeable about published increased risks and the various ways symptoms of an ICH may present. One of the EL-PFDD panel members and video contributors spoke about their child who died suddenly and unexpectedly from an ICH secondary to ITP said “we [he and his wife] want to create this environment and perhaps change protocol, guidelines, so hopefully another family doesn’t have to go through this event” (Video 3).

Possible solution: Since knowledge in medicine expands rapidly, professional organizations for hematologists could consider implementing updated educational initiatives based on evidence based best practices that are mandatory for all hematologists. Consider also ensuring all front-line health care providers are trained to deal with atypical ITP, such as chronic severe thrombocytopenia in association with moderate-severe bleeding.

Diagnostic improvements

- Patients want to understand if their ITP is primary or secondary, and they wish to receive their diagnosis in a timely manner.

Since ITP is a diagnosis of exclusion (42,44) it can be challenging to confirm whether ITP is primary or due to an underlying secondary cause. Most patients want to understand if their thrombocytopenia is genetic and if there are risks to other family members. Genetic testing for thrombocytopenia is available, and patients are interested in learning more about when such testing would be appropriate for them. Patients also want their diagnosis in a timely manner. Using data from our registry, 32% had to wait for over a year after the onset of symptoms to be officially diagnosed with ITP (5).

Possible solution: Consider genetic testing for chronic ITP patients, particularly children who are unresponsive to steroids. To provide optimal knowledge of the risks and benefits of genetic testing, providers could consider referring their patients to a genetic counsellor to discuss if testing is relevant for them.

Treatments

- There is an urgent unmet need for new and efficient therapies, especially those that target unexplored disease mechanisms, to easily and safely treat and manage ITP and improve the quality of life for ITP patients (27,55).

One of the greatest frustrations expressed from patients regarding managing their ITP is the high likelihood of relapse following standard first-line therapies (steroids and IVIG) that will lose their clinical effectiveness often long before there side-effects resolve. Often, the side-effects associated with treating ITP outweigh the decision to treat a low platelet count, leaving some patients at risk for bleeding. A panellist at the EL-PFDD meeting who had spent 8 years training for wrestling on a varsity team and a career in the military stated: “I was crushed… I gained 18 pounds from prednisone in one month. I started getting bullied by the people I had wrestled with all those years. I was devastated” (Video 1). Another panellist stated: “So many of us hang our hopes on the next treatment” (Video 2). ITP patients and their physicians currently cycle through a series of treatment options, each with different therapeutic mechanisms (12). In the end, patients are looking for a treatment that lasts and does not negatively impact their QoL (27). Ideally, therapies should have fewer side effects and patients should not feel forced into splenectomy or continued steroid use or run out of treatment choices.

Possible solution: Health care providers treating ITP patients could consider taking any opportunity they are presented with to advocate for their patients for innovative ways to treat ITP. This possible solution also applies when talking about access issues and better treatments for pediatric ITP patients.

Access issues

- Patients want their health care providers to advocate to change existing policies and enable ITP patients to access the most appropriate treatments when needed.

Access to newer ITP therapies can be a challenge depending on insurance coverage and country of origin. Sometimes, the ‘most appropriate’ treatment to improve disease symptoms and HRQoL cannot be accessed until the ITP patient has demonstrated previous failure to a less effective therapy, or there is a need to select from treatment lines in a step-like fashion which does not meet current standard guidelines for ITP management. Public drug funding programs are limited and often do not cover off-label use. Patients often need private insurance or have to pay out-of-pocket costs. For minors, drug coverage may end the moment they finish school or turn 21–25 years of age if they are currently using a parents’ private insurance plan. PDSA patient members (Videos 1 and 2) outline the importance of obtaining the ‘most appropriate’ therapy.

Patients are motivated to participate in anything that could help control their platelet count and ITP symptoms and believe that limited/no access to clinical trials or newer treatments is a gap in care due to previously established clinical end-points. Currently, within our patient registry, 93% of participants have indicated they would be willing to be part of a clinical trial for ITP. On-going research, clinical studies, and therapeutic development are vital to improving the treatment landscape, giving patients more choices with which to live their lives fully, with few side-effects and long-term control of their ITP (5). Participation in research also allows for priorities of rare-disease patients to be recognized. Often access to clinical trials and research opportunities depends on geography and whether their health care provider is aware of them. Patients want studies to address the burden of their disease beyond the platelet count. Patients want increased awareness in public and professional health communities and comprehensive treatment centers to improve care and outcomes. Raising awareness for ITP in the clinical sphere is crucial in better informing medical professionals, and raising public awareness for ITP is vital in empowering patients to take control of their disease. Collaboration with ITP experts and establishing centers of excellence worldwide for ITP and other platelet disorders could mitigate the risk posed by non-specialists treating thrombocytopenia patients, thus improving treatment options, therapeutic experience, and quality of life.

More treatment options for children with ITP

- While treatment options are expanding for children with ITP many of the newer innovative therapies are approved for use only in adults, but not for children.

Young ITP patients share the financial challenges involved in accessing new treatments, and how long it took to obtain effective treatment (Video 1). Since there are less children with ITP requiring treatment compared to adults, the fear is that effective therapies will continue to be out of reach for many. Access to additional therapeutic options could reduce the emotional toll the disease has on children, who often suffer the most from restricted activities (20).

Acknowledgement of their ITP experience

- Patients want their providers to have a better understanding of their disease experience.

Everyone’s journey with ITP is unique. For many adults and children with ITP, the impact on their significant levels of fatigue, anxiety, and depression deserve a greater appreciation because it affects all aspects of their HRQoL. Patients are the experts on what it’s like to live with ITP and can best identify and articulate the impact ITP has on their everyday life. They want their providers to listen to their symptoms and challenges without judgement or correction. Many patients report their fatigue is not recognized as part of their ITP or that the emotional toll ITP has on their life is not recognized or valued (17,18,24,30). This is a tragedy considering these are the effects of living with ITP that matter most to patients.

Possible solution: Consider asking ITP patients at each visit how they have been doing mental health wise, and physically, in addition to asking about sports and bleeding events. When patient’s report fatigue, consider refraining from saying fatigue isn’t part of ITP even though its pathophysiology is not well understood.

Summary

While it may seem like ITP is a simple ‘benign’ disease on the surface, nothing could be farther from the truth. There are many complexities associated with ITP regarding disease etiology, risks, treatment responses, and heterogeneity in clinical symptoms. This highlights the need for greater attention from the medical community. Knowledge about ITP continues to expand requiring physicians who treat ITP patients to stay current in best practices for ITP. Health care providers are encouraged to work with their ITP patients who are the experts on living with this rare disorder.

Aside from the constant risk for serious bleeding, patients experience both physical and emotional consequences living with their disease on a daily basis, negatively impacting their overall quality of life. In addition to debilitating fatigue (17,27), high levels of anxiety and depression are experienced by the majority of ITP patients, despite having good social support systems in place (7) and reporting a good quality of life (5). The levels of anxiety, pain, and depression reported within the ITP registry participants exceeds what is reported in the general population (37,38). For many ITP patients, these symptoms are front and center among their concerns, rather than the clinical measures of platelet counts. Therefore, it’s important to ask patients not only about their bleeding symptoms, but also how they are doing on both a physical and emotional level, particularly with regards to dealing with their ITP. Health care providers are also encouraged to make time and be open to listening to their ITP patients about what they are dealing with and to ask targeted questions to elicit how their patient is really coping with their ITP.

High levels of anxiety and depression could reflect the unpredictability of ITP and the acceptance that the diagnosis comes with a constant risk of bleeding among those living with it. Levels of fatigue reported here among ITP patients is comparable to the level of fatigue reported in general in autoimmune disease groups (35). Fatigue can interfere with patient’s ability to show up in their own life and participate in regular routines and work or attend school. Guilt and disappointment over limited abilities and restricted activities due to a low platelet count likely further contribute to the negative emotional burden on ITP patients. The symptoms that accompany the disease and the constant monitoring of platelet counts interfere with daily activities and lead to anxiety, fear, depression, embarrassment over unexplained bruises or blood blisters, isolation, inadequacy, and frustration with a patients’ inability to control their body and their health. To minimize bleeding risks, patients with ITP need to routinely weight the risks associated with their daily activities, and sometime forgo travelling or participant in sporting or social events. ITP presents an additional layer of complexity for patients who require a specialized medical procedure or surgery, or become pregnant, or find themselves in the care of a specialist health care provider in an emergency situation who might not be current in their knowledge about ITP. Together, this demonstrates the multifaceted effect ITP has on overall QoL.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (John W. Semple and Rick Kapur) for the series “Treatment of Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP)” published in Annals of Blood. The article was sent for external peer review organized by the Guest Editors and the editorial office.

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aob-20-57

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aob-20-57). The series “Treatment of Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP)” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare, however it has been declared that one of the authors had a child who passed away from immune thrombocytopenia. Reporting grants and other from Amgen, grants from Argenx, grants and other from Pfizer, grants from Principia, grants from Rigel, grants and other from UCB, grants and other from Novartis, grants from CSL Behring, outside the submitted work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring that questions related to the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Consent was obtained from each participant who submitted a video for the purpose of this study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Semple JW, Provan D, Bernadette M, et al. Recent progress in understanding the pathogenesis of immune thrombocytopenia. Curr Opin Hematol 2010;17:590-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newland A, Godeau B, Priego V, et al. Remission and platelet responses with romiplostim in primary immune thrombocytopenia: final results from a phase 2 study. Br J Haematol 2016;172:262-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salma A. Emerging drugs for immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Salama A Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2017;22:27-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Platelet Disorder Support Association Voice of The Patient Report (VoP) [Internet]. Ohio c.2019 [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available online: https://pdsa.org/voice-of-the-patient

- Kruse A, Kruse C, Potthast N, et al. Quality of life and demographics of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP); Data from the platelet disorder support association (PDSA) patient registry. HemaSphere 2019;3:1009. [Crossref]

- Kruse A, Kruse C, Potthast N, et al. Mental Health and Treatment in Patients with Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP); Data from the Platelet Disorder Support Association (PDSA) Patient Registry. Blood 2019;134 Suppl_1:2362.

- DiRaimo J, Kruse C, Lambert M, et al. Mental health and physical function in pediatric immune thrombocytopenia (ITP): Quality of life data from the platelet disorder support association (PDSA) patient registry. 2020. HemaSphere [06/12/20; 294150; EP1669]. Available online: https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2020/eha25th/294150/caroline.kruse.mental.health.and.physical.function.in.pediatric.immune.html?f=listing%3D3%2Abrowseby%3D8%2Asortby%3D1%2Amedia%3D1

- NIH PROMIS – HealthMeasures [Internet]. Northwestern University; [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis.

- Despotovic JM, Grimes AB. Pediatric ITP: is it different from adult ITP? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2018;2018:405-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold DM. Bleeding complications in immune thrombocytopenia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2015;2015:237-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mithoowani S, Arnold DM. First-line therapy for immune thrombocytopenia. Hamostaseologie 2019;39:259-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zufferey A, Kapur R, Semple J. Pathogenesis and therapeutic mechanisms in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). J Clin Med 2017;6:1-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nørgaard M, Cetin K, Maegbaek ML, et al. Risk of arterial thrombotic and venous thromboembolic events in patients with primary chronic immune thrombocytopenia: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Br J Haematol 2016;174:639-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bussel J, Kruse A, Kruse C, et al. The burden of disease and IMPACT of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) on patients: Results from an ITP survey. Blood 2019;134 Suppl_1:1076.

- Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) [Internet], c. 2018 October 31 [cited on 2020 Nov 18]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/index.htm

- Suvajdzic N, Zivkovic R, Djunic I, et al. Health-related quality of life in adult patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia in Serbia. Platelets 2014;25:467-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper N, Ghanima W, Provan D, et al. The burden of disease and impact of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the ITP world impact survey (I-WISH). 2018; HemaSphere [06/15/18; 215096; PF654]. Available online: https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2018/stockholm/215096/nichola.cooper.the.burden.of.disease.and.impact.of.immune.thrombocytopenia.html

- Kruse C, Kruse A, Watson S, et al. Patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) frequently experience severe fatigue but is it under-recognized by physicians: results from the ITP World Impact Survey (I-WISh). Blood 2018;132:2273. [Crossref]

- Zilber R, Bortz AP, Yacobovich J, et al. Analysis of health-related quality of life in children with immune thrombocytopenia and their parents using kids’ITP tools. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:2-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Flores A, Klaassen RJ, Buchanan GR, et al. Patterns and influences in health-related quality of life in children with immune thrombocytopenia: A study from the Dallas ITP cohort. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017;64:e26405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giordano P, Lassandro G, di Melo NA, et al. A narrative approach to describe QoL in children with chronic ITP. Front Pediatr 2019;7:163. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper N, Kruse A, Kruse C, et al. Results from the ITP World Impact Survey (I-WISh): Patients with immune thrombocytopenia experience impaired quality of life regarding daily activities, social interactions, emotional well-being, and working lives. Blood 2018;132 Suppl 1:4804. [Crossref]

- Cooper N, Kruse A, Kruse C, et al. A patient’s perspective on impact of immune thrombocytopenia and emotional wellbeing: ITP World Impact Survey (I-WISh). HemaSphere [06/12/20; 294135; EP1654]. Available online: https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2020/eha25th/294135/

- Bussel J, Ghanima W, Cooper N, et al. Higher symptom burden in patients with immune thrombocytopenia from the ITP World Impact Survey (I-WISh). HemaSphere. [06/12/20; 294123; EP1642]. Available online: https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2020/eha25th/294123/

- McMillan R, Bussel JB, George JN, et al. Self-reported health-related quality of life in adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol 2008;83:150-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cuker A, Prak E, Cines DB. Can immune thrombocytopenia be cured with medical therapy? Semin Thromb Hemost 2015;41:395-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kruse A. Beyond the Platelet Count [Internet], c.2019. [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: http://pdsa.org/images/BeyondThePlateletCount.pdf

- Bussel J, Ghanima W, Tomiyama Y, et al. Patients’ and Physicians’ Perspectives on Treatment in ITP – A Multi-Country Perspective: Results From the ITP World Impact Survey (I-WISh). Blood 2019;134 Suppl_1: 1097.

- Newland A, Lee E, McDonald V, et al. Fostamatinib for persistent/chronic adult immune thrombocytopenia. Immunotherapy 2018;10:9-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newton JL, Reese JA, Watson SI, et al. Fatigue in adult patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Eur J Haematol 2011;86:420-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sestøl HG, Trangbaek SM, Bussel JB, et al. Health-related quality of life in adult primary immune thrombocytopenia. Expert Rev Hematol 2018;11:975-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grace RF, Klaassen R, Shimano K, et al. Fatigue in children and adolescents with immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol 2020;191:98-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarantino MD, Mathias S, Synder C, et al. Impact of ITP on physician visits and workplace productivity. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:319-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mathias SD, Gao SK, Miller KL, et al. Impact of chronic Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) on health-related quality of life: a conceptual model starting with the patient perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association. Profound, debilitating fatigue found to be a major issue for autoimmune disease patients in new national survey. ScienceDaily. [cited on 2020 Nov 18]. Available online: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150323105245.htm

- Grout RW, Thompson-Fleming R, Carroll A, et al. Prevalence of pain reports in pediatric primary care and association with demographics, body mass, and exam findings: a cross sectional study. BMC Pediatrics 2018;18:363. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America [Internet]. Maryland USA. [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available online: https://adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics

- National Alliance on Mental Illness [Internet]. Virginia, USA [cited 2020 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions

- Cuijpers P, Beekman ATF, Renolds CFI. Preventing depression. A global priority. JAMA 2012;307:1033-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guidry JA, George JN, Vesely S, et al. Corticosteroid side-effects and risk for bleeding in immune thrombocytopenia purpura: patient and hematologist perspectives. Eur J Haematol 2009;83:175-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gavin F. An imaginative partnership: Parents and their doctors who care for their children. Paediatr Child Health 2009;14:295-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matzdorff A, Meyer O, Ostermann H, et al. Immune thrombocytopenia – current diagnostics and therapy: Recommendations of a joint working group of DGHO, OGHO, SGH, GPOH, and DGTI. Oncol Res Treat 2018;41 Suppl 5:1-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neunert C, Terrell DR, Arnold D, et al. American society of hematology 2019 guidelines for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv 2019;3:3829-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, et al. Updated international consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv 2019;3:3780-817. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stanarević Katavić S. Health information behaviour of rare disease patients: seeking, finding and sharing health information. Health Info Libr J 2019;36:341-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bussel J, Tkacz J, Manjelievskaia J, et al. Long-term overuse of corticosteroids in patients with immune thrombocytopenia: a real-world analysis of a us claims database. 2020. HemaSphere [06/12/20, 294115; EP1633]. Available online: https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2020/eha25th/294115/adam.cuker.long-term.overuse.of.corticosteroids.in.patients.with.immune.html?f=menu%3D6*browseby%3D8*sortby%3D2*media%3D3*ce_id%3D1766*ot_id%3D23244*marker%3D757

- Lambert MP, Grace R, Despotovic J, et al. Watchful waiting for pediatric ITP: what does that actually mean? Platelet Disorder Support Association [Internet]; c. 2018 July 1. [cited 2020 September 1]. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org/images/WatchfulWaitingPediatric.pdf

- Neunert C. Individualized treatment for immune thrombocytopenia: Predicting bleeding risk. Semin Hematol 2013;1 Suppl_1:S55-S-57.

- Psaila B, Petrovic A, Page LK, et al. Intercranial hemorrhage (ICH) in children with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP): A study of 40 cases. Blood 2009;114:4777-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hato T, Shimada N, Kurata Y, et al. Risk factors for skin, mucosal, and organ bleeding in adults with ITP: a nationwide study in Japan. Blood Adv 2020;4:1648-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mithoowani S, Cervi A, Shah N, et al. Management of major bleeds in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:1783-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muda Z, Ibrahim H, Rahman JA, et al. Spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in children with chronic immune thrombocytopenia purpura. Med J Malaysia 2014;69:288-90. [PubMed]

- Zhao P, Hou M, Liu Y, et al. Risk stratification and outcomes of intracranial hemorrhage in patients with immune thrombocytopenia under 60 years of age. Platelets 2020. Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uetz B, Wawer A, Nathrath M, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP): Fatal course in spite of maximum therapy. Klin Padiatr 2010;222:383-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Izak M, Bussel JB. Management of thrombocytopenia. F1000Prime Rep 2014;6:45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Kruse C, Kruse A, DiRaimo J. Immune thrombocytopenia: the patient’s perspective. Ann Blood 2021;6:9.