Prevalence and associates of anemia in adult men and women urban dwellers in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study in a Sub-Saharan setting

Introduction

Anemia is a public health problem worldwide with the greatest burden in lower-middle income countries (LMICs) in Central and West Africa, and in South Asia. It is associated with a high morbidity and mortality in children and women (1). About 1.62 billion people are estimated to have anemia (2), and close to 800 million are infant and pregnancy related (1). Iron deficiency has been shown to be the most frequent cause of anemia (3). The high disease burden in LMICs is contrasted with the paucity of representative data. Most epidemiologic studies have been reported in children and pregnant women (4,5). Anemia in few special groups has also been reported such as in those with diabetics, heart failure, older than 50 years, and in the emergency setting (6-10). Anemia is associated with poor outcome in patients with heart failure (7,8). Few largescale community studies have been reported in LMICs especially in east Africa (11). In Cameroon, central Africa sub-region, the burden of anemia has been reported in a group of patients with diabetes in an urban tertiary hospital, with emphasis on those with chronic kidney disease (6). A high rate of anemia was also noted even in those without chronic kidney disease. However, these findings cannot be extrapolated to the general population. The true burden of anemia in the community is therefore not known in our setting.

In this cross-sectional descriptive and analytic study, we sought to assess the prevalence and determinants of anemia in a group of urban dwelling men and women from Cameroon, a LMIC in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

Methods

Ethical statement

Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaounde 1, Cameroon. We carried out this work in accordance with the declarations of Helsinki (12). All the participants gave their written consent. We report this work using the STROBE checklist (13).

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional descriptive and analytic study was carried-out in a specialist Cardiology clinic between October and November 2016, in Yaounde—the Capital city of Cameroon, SSA. The population of Yaounde is estimated at two million inhabitants.

Participants

These were workers of a high social standard state corporation who underwent an annual health checkup. Their social standards were more than that of the average Cameroonian probably because of a better pay package and social advantages. We included all consenting adults aged ≥18 years of both sexes.

Variables

The participants were invited to come to the clinic between eight and nine o’clock in the morning after an overnight fasting for at least eight hours. We collected following data via a face-to-face interview—demographics (age and sex), personal history (diabetes, hypertension, alcohol use, tobacco use, dyslipidemia, drug use), lifestyle (low risk diet, physical activity), family history (diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction), and symptoms related to anemia (asthenia, palpitation, dyspnea, headache). We then carried-out the following measurements—anthropometry (height, weight, abdominal circumference, and resting blood pressure), and drew blood for biochemistry assays (glycemia, HbA1c, serum creatinine, lipid profile, serum uric acid, and full blood count).

Data sources and measurements: Their weight (w) was measured (kg) with an electronic scale in with no shoes and in light clothing, and their height (h) was measured (m) with a stadiometer close to the scalp. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as w/h2. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. The abdominal circumference was measured with a measuring tape in the standing position mid-way between the iliac crest and the inferior costal margin, mid-axillary line. Abdominal Obesity was defined as >94 cm in men and >80 cm in women (IDF criteria). Their blood pressure (BP) was measured twice on both arms after 10 minutes of rest in the sitting position, with an electronic device (Omron®) using a standard adult arm cuff. The average of the highest recording was considered for classifying the BP. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) readings >140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure readings (DBP) >90 mmHg was considered as having elevated BP. The hemoglobin (Hb) level was assessed using an automate analyzer. We defined anemia using the WHO criteria [3] as an Hb <13 g/dL in males, and <12 g/dL in females. We further classified anemia as mild (Hb: 11–12.9 g/dL in men, and Hb: 11–11.9 g/dL in women), moderate (Hb: 8–10.9 g/dL), and severe (Hb <8 g/dL). We measured the glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and fasting blood glucose (FBG) using the Glucose Oxidase method. An HbA1c ≥6.5% and/or FBG ≥126 mg/dL or a participant on anti-diabetes medication was considered as having diabetes. Other biochemical blood tests were carried-out using standard methods. Dyslipidemia (hypercholesterolemia) was present if a participant has at least one of the following lipid anomaly: total cholesterol >2 g/L, LDLc >1 g/L, Triglyceride >1.5 g/L, and HDLc <0.4 g/L for men and <0.5 g/L for women. Hyperuricemia was present if serum uric acid was >70 mg/L in males, and >60 mg/L in females. A participant was considered a current smoker if he/she used tobacco or it products within the past three years. Alcohol consumption was limited to its use (yes/no).

Outcome data

The main outcome was the presence and severity of anemia. Other variables studied were the components of the metabolic syndrome, and the 10-year cardiovascular risks (risk estimated using the Framingham risk score calculator) as factors potentially associated with anemia.

Study size

This was a cross-sectional descriptive and analytic study involving a group of workers in Cameroon, in the central region of Sub-Saharan Africa. A convenient sample of all eligible participants was considered for this study. The expected number of participants was about 260.

Statistical methods

The data were analyzed using the software Epi-Info version 7. We have presented the baseline characteristics according to the presence or absence of anemia. We have presented discrete variables as frequencies and proportions with their 95% confidence intervals. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations. Differences between proportions were compared using Chi-square or Fischer exact tests where applicable. The differences between mean values were compared using two-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test where applicable. We assessed the association of some clinical and biochemical parameters with anemia using odds ratios (OR). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for the observed differences or associations.

Results

Participants and descriptive data

A total of 236 participants were screened, of whom 137 [58.1%, (95% CI: 51.5–64.4)] were males, and 99 [41.9%, (95% CI: 35.6–48.5)] were females. Their mean age was 45.4±10.6 years (males: 46.3±10.2 versus females: 44.1±11.1, P=0.118), and ranged from 23 to 62 years. The mean values of the clinical and biochemical parameters according to the presence or absence of anemia are shown in Table 1. The overall mean Hb was 12.7±1.5 g/L (males: 13.5±1.1 g/L versus females: 11.7±1.2 g/L, P<0.001). Those with anemia had significantly lower mean platelet counts, serum creatinine, and lipid parameters. At least one complaint was reported by 104 [44.1%, (95% CI: 37.6–50.7)] of the participant. Headache was reported in 8 (3.4%), nonspecific chest pain in 18 (7.6%), dyspnea in 16 (6.8%), palpitation in 34 (14.4%), and snoring in 58 (24.6%) of the participants. Low intensity (2/6 and 3/6) heart murmur was heard in 13 (5.5%) participants—7/93 of those with anaemia, and 6/143 of those without anaemia. A history of menorrhagia on uterine fibroids was reported in 3 (3%) females, 1 woman was 6-week pregnant.

Table 1

| Variables, mean (SD) | Overall (n=236) | Anemia | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=93) | No (n=143) | |||

| Age (years) | 45.4 (10.6) | 45.9 (10.6) | 45 (10.6) | 0.521 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.6 (4.7) | 28.4 (4.7) | 28.7 (4.7) | 0.667 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 93.9 (12.4) | 92.9 (13.2) | 94.5 (11.8) | 0.341 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135 (21.8) | 135.2 (19.5) | 134.8 (23.2) | 0.902 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.5 [13] | 79 (11.5) | 79.9 (13.8) | 0.577 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | 71.3 [11] | 71.4 (11.2) | 71.2 (10.8) | 0.906 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.7 (1.5) | 11.5 (1.2) | 13.6 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (counts/mL) | 200,003.9 | 220,853.3 | 186,495.8 | 0.002 |

| White blood cells (counts/mL) | 4,979.01 | 5,177.6 | 4,849.9 | 0.512 |

| Glycemia (g/L) | 0.86 (0.2) | 0.86 (0.2) | 0.86 (0.1) | 0.843 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%) | 5.4 (0.95) | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.4 (0.8) | 0.858 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/L) | 9.5 (3.01) | 8.8 (2.7) | 9.9 (3.1) | 0.011 |

| Total cholesterol (g/L) | 1.98 (0.4) | 1.96 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 0.369 |

| HDL cholesterol (g/L) | 0.63 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.58 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (g/L) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | 0.009 |

| Triglycerides (g/L) | 0.81 (0.8) | 0.67 (0.3) | 0.9 (1.01) | 0.036 |

| Cholesterol/HDLc ratio | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.7 (1.04) | <0.001 |

| 10-year cardiovascular risk | 11.6 (9.8) | 11.2 (9.99) | 11.8 (9.7) | 0.674 |

Outcome data and main results

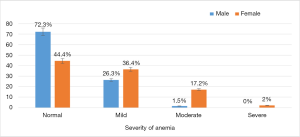

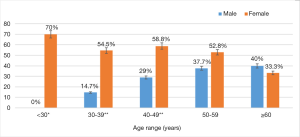

Overall, anemia was seen in 93 [39.3%, (95% CI: 33.1–46)] participants—38 [27.7%, (95% CI: 20.4–36)] males, and 55 [55.6%, (95% CI: 45.2–65.5)] females. The distribution of anemia according to sex and age category is shown in Figure 1. The prevalence of anemia was significantly higher in women ≤40 years of age. There was no statistical significance in the prevalence rate of anemia between 50 and 63 years. Overall, the severity of anemia was mild in 72 [30.5%, (95% CI: 24.7–36.8)], moderate in 19 [8.1%, (95% CI: 4.9–12.3)], and severe in 2 [0.8%, (95% CI: 0.1–3)] participants. The distribution of anemia according to sex and severity is shown in Figure 2. Anemia was mostly mild in men, and mild to moderate in women (P<0.001 for trend). The factors associated with anemia are shown in Table 2. Female sex was associated with a high odds of having anemia (OR: 3.3; P<0.001), while tobacco use (OR: 0.3; P=0.018) and high atherogenicity index (OR: 0.5; P=0.054) appeared to be protective against anemia. After adjusting for sex, tobacco use was not associated with a lower odds of anemia [aOR: 0.5, (95% CI: 0.2–1.3), P=0.094].

Table 2

| Variables | Overall, n (%) | Anemia, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| >50 | 102 (43.2) | 44 (43.1) | 58 (56.9) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 0.306 |

| <50 | 134 (56.8) | 49 (36.6) | 85 (63.4) | 1 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 99 (41.9) | 55 (55.6) | 44 (44.4) | 3.3 (1.9–5.6) | <0.001 |

| Male | 137 (58.1) | 38 (27.7) | 99 (72.3) | 1 | |

| Symptom(s) | |||||

| Yes | 104 (44.1) | 44 (42.3) | 60 (57.7) | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | 0.418 |

| No | 132 (55.9) | 49 (37.1) | 83 (62.9) | 1 | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| Yes | 137 (58.1) | 49 (35.8) | 88 (64.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.178 |

| No | 99 (41.9) | 44 (44.4) | 55 (55.6) | 1 | |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| Yes | 27 (11.4) | 5 (18.5) | 22 (81.5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 0.018 |

| No | 209 (88.6) | 88 (42.1) | 121 (57.9) | 1 | |

| High adiposity | |||||

| Yes | 150 (64.4) | 65 (43.3) | 85 (56.7) | 1.6 (0.9 – 2.8) | 0.106 |

| No | 83 (35.6) | 27 (32.5) | 56 (67.5) | 1 | |

| Hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 76 (32.2) | 34 (44.7) | 42 (55.3) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 0.248 |

| No | 160 (67.8) | 59 (36.9) | 101 (63.1) | 1 | |

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 14 (5.9) | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) | 0.8 (0.3–2.6) | 0.771 |

| No | 222 (94.1) | 88 (39.6) | 134 (60.4) | 1 | |

| Hyperuricemia | |||||

| Yes | 66 (28.0) | 21 (31.8) | 45 (68.2) | 0.6 90.3–1.2) | 0.137 |

| No | 170 (72.0) | 72 (42.4) | 98 (57.6) | 1 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||

| Yes | 6 (2.5) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 1.6 (0.3–7.9) | 0.591 |

| No | 230 (97.5) | 90 (39.1) | 140 (60.9) | 1 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||||

| Yes | 19 (8.1) | 6 (31.6) | 13 (68.4) | 0.7 (0.3–1.9) | 0.467 |

| No | 217 (91.9) | 87 (40.1) | 130 (59.9) | 1 | |

| High atherogenicity index | |||||

| Yes | 39 (16.5) | 10 (25.6) | 29 (74.4) | 0.5 (0.2–1.02) | 0.054 |

| No | 197 (83.5) | 83 (42.1) | 114 (57.9) | 1 | |

| Metabolic syndrome | |||||

| Yes | 97 (41.1) | 38 (39.2) | 59 (60.8) | 0.98 (0.6–1.7) | 0.951 |

| No | 139 (58.9) | 55 (39.6) | 84 (60.4) | 1 | |

| High 10-year risk | |||||

| Yes | 160 (67.8) | 60 (37.5) | 100 (62.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.384 |

| No | 76 (32.2) | 33 (43.4) | 43 (56.6) | 1 | |

Discussion

We carried out this cross-sectional descriptive and analytic study with the aim of assessing the prevalence and severity of anemia in urban dwelling adult men and women in Cameroon, a lower-middle income country (LMIC) in SSA. The prevalence of anemia was very high in these high social profile workers. One-in-four men had mild anemia, and more than half of women had mild to moderate anemia, with the greatest burden in women less than forty years of age.

This study should be interpreted in the light of some limitations. The participants were urban dwelling men and women with a high social profile. Our findings could not be extrapolated to those with a low social status, in children, and in the rural settings. We assessed anemia by measuring the Hb only according to WHO criteria (3). Data on cell volume and corpuscular concentration of Hb was not captured, thus we were not able to categorize the anemia based on cell size and color. We did not measure the iron reserves, vitamin B12, folic acid, vitamin A, CRP, and the search for chronic inflammations and hemoglobinopathy, to give an in-depth picture of anemia (3). We did not adjust Hb for smoking status and altitude, which could lead to underestimates of the burden of anemia (3). Despite these limitations, this study sheds light on the burden of anemia in our urban setting.

Few community studies have addressed the problem of anemia in our setting. Feteh et al. (6) reported a prevalence of 41.4% in a large cohort of those living with diabetes seen at an urban tertiary hospital. Tchente et al. (4) reported a prevalence of 39.8% in a group of pregnant women in the same setting. These findings, coupled with ours shows that anemia is a moderate to severe public health problem in our setting (2). The burden of anemia was highest in females less than 40 years, and gradually declined with increasing age. The burden of anemia increased gradually with age in men, with higher rates than women after 60 years. A higher prevalence of anemia in people older than 50 years was reported by Mugisha et al. (9). This pattern could be explained by excessive iron loss in menstruating women, and occult blood loss in ageing men. Compared to special groups, Makubi et al. (8) reported a prevalence of 57% in those with heart failure in Tanzania. The pattern of disease was that of the ageing population as shown in our study. Ikama et al. (7) reported a prevalence of 42% in Congo-Brazzaville. In the emergency setting, Mukaya et al. (10) reported a prevalence of 64.6%, with prevalent symptoms of anemia. The participants in this study worked in a high social standard state corporation, most of whom occupy administrative positions, and probably have a good salary. High socio-economic status and urban lifestyle as risk factors for anemia was reported by Adamu et al. (11). This interaction is not well understood. Those with anemia had a significantly favorable lipid panel (mean values), but no significant association was found on univariate analysis. A weak but significant correlation was reported by Feteh et al. (6) in a group of people with diabetes, and a significant inverse or favorable association of cholesterol and anemia was reported by Makubi et al. (8) in a group of patients with heart failure. This interaction needs to be studies further. In all, age and gender significantly modulates the prevalence of anemia. Large scale studies of anemia in urban and rural populations of Cameroon are needed for a better understanding.

Conclusions

The prevalence of anemia was very high in these high social profile workers. One-in-four men had mild anemia, and more than half of women had mild to moderate anemia, with the greatest burden in women less than 40 years of age.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support staff of “Centre Medical de l'Hippodrome (CMH)”, Yaounde, for assisting with participant enrollment.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aob.2018.05.04). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the manuscript and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaounde 1, Cameroon (approval ID: May-9-2016/UY1/FMSB/VDRC/CD). All the participants gave their written consent.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995-2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1:e16-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005: WHO global database on anaemia. 2008 [cited 2017 Oct 7]; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43894/1/9789241596657_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Geneva: Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, WHO, 2011.

- Tchente CN, Tsakeu EN, Nguea AG, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia in pregnant women attending the General Hospital in Douala. Pan Afr Med J 2016;25:133. [PubMed]

- Obai G, Odongo P, Wanyama R. Prevalence of anaemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Gulu and Hoima Regional Hospitals in Uganda: A cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 201611;16:76.

- Feteh VF, Choukem SP, Kengne AP, et al. Anemia in type 2 diabetic patients and correlation with kidney function in a tertiary care sub-Saharan African hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2016;17:29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ikama MS, Nsitou BM, Kocko I, et al. Prevalence of anaemia among patients with heart failure at the Brazzaville University Hospital. Cardiovasc J Afr 2015;26:140-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Makubi A, Hage C, Lwakatare J, et al. Prevalence and prognostic implications of anaemia and iron deficiency in Tanzanian patients with heart failure. Heart 2015;101:592-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mugisha JO, Baisley K, Asiki G, et al. Prevalence, types, risk factors and clinical correlates of anaemia in older people in a rural Ugandan population. PLoS One 2013;8:e78394 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mukaya JE, Ddungu H, Ssali F, et al. Prevalence and morphological types of anaemia and hookworm infestation in the medical emergency ward, Mulago Hospital, Uganda. S Afr Med J 2009;99:881-6. [PubMed]

- Adamu AL, Crampin A, Kayuni N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for anemia severity and type in Malawian men and women: urban and rural differences. Popul Health Metr 2017;15:12. [Crossref]

- . World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997;277:925-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:867-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Jingi AM, Kuate-Mfeukeu L, Hamadou B, Ateba NA, Nganou CN, Amougou SN, Guela-Wawo E, Kingue S. Prevalence and associates of anemia in adult men and women urban dwellers in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study in a Sub-Saharan setting. Ann Blood 2018;3:34.